a true story about the last of us & when we need ladders

Date:

January 7, 2024

I didn’t play video games for 20 years. This is how The Last of Us brought me back in more ways than one.

spoiler alert: this essay contains spoilers for The Last of Us I and II.

*

an open letter to Neil Druckmann (the creator of The Last of Us):

Dear Neil,

You made me kill a nurse but you also inspired my largest tattoo to date. So this is a thank you letter. But not like the kind you feel obligated to write after a wedding. This is the kind you can’t not write, at least in your own head, when something changes you, brings back a part of you you thought was dead.

*

When I was eight my parents led me and my brother to the playroom to see what Santa had brought. There was wrapping paper taped over one section of a shelf. Together, my brother and I ripped open the paper to reveal a Nintendo. I screamed. Screamed. Screamed!

It was the first gaming system we ever had. My brother and I spent the rest of the day on this pad it came with, running as fast as we could on red and blue dots to make our men on the screen run and run and run. I suppose we were racing each other, but it always felt like we were running together, on the same team.

*

By the time I stepped into The Last of Us world, almost 30 years after the wrapping paper and the screaming, I hadn’t held a video game controller in decades. But after The Last of Us TV show ended, I wanted more. I was curious. I wanted to know what it would feel like to get closer.

While visiting my brother who is all grown up now with a house in Texas and two kids of his own (who both love Mario…my niece carts a Mario doll in a pink stroller), I asked him if I could play just a few minutes of the game, if he would walk me through how to do it. He was thrilled and we sat down together in his dark game room and he placed headphones over my ears.

Suddenly I wasn’t in Texas anymore. I wasn’t me anymore. I was a girl with short-cropped blonde hair. A teenager. Clever. Searching, searching, searching. Chaos outside. Maybe fire.

I was looking for my dad.

I checked the bathroom. There were two gray towels hung haphazardly over the towel rack. I stopped. I stared.

The towels told a story. The towels were foreshadowing. The towels would never be used again.

*

I loved Donkey Kong as a young teenager, especially the feeling of beating the first level. It felt just like the running on the pad. Go go go go until you reach the end. The feeling of not losing, of not dying.

I also loved the second level in Donkey Kong, swinging on ropes in constant rain. I felt invincible, alive, like I could do anything, be anything.

Then I started dying. A lot.

But no worries. Just begin again. Start over. Go back to where you last saved.

Then there were hard levels, mine cart levels, where I just kept falling. Falling. Falling. Falling. Falling.

Then I’d get farther than I’d ever gotten before—finally—and then. I’d die.

I’d get frustrated. Unhappy. On a Saturday.

Isn’t this supposed to be fun?

When I wasn’t having fun anymore, I stopped.

*

Eventually I stopped staring at the towels and I found my dad. We got in a truck with my uncle and we tried to outrun the fear and the fire. We crashed, though. And when we did, I broke my leg. My dad carried me. I am now the dad. I carry the girl I once was. I run and run and run. I die. I die. I die again.

I ask for help. My brother tells me to run faster, to try going down another alley, to not let too much distance grow between me and my brother in the game whom I am following.

I keep going.

But then, my daughter is shot. The girl I used to be dies.

*

I also really liked Crash Bandicoot as a young teen. But once again, after the triumph of the first level ended, I kept dying. Over and over.

This didn’t seem to bother my brother, though. He seemed to be always having fun playing games, even when he lost. I wasn’t.

I always thought reading was fun, though. He didn’t.

Some things are fun to some and not fun to others, I reasoned. He must also be naturally better at games than I am. He can figure out things I can’t. I’m obviously not good at this.

We decide.

Identify.

I am a reader, not a gamer, I decide.

*

I had never been traumatized until the winter of 2018. It’s still too raw to talk about, but it was the kind of trauma that fills you almost daily with a kind of desperation that if only you could have found a secret cave with a save brick to jump on, a place to go back to, to erase everything that just happened.

I was not okay.

The kind of not okay where you are so traumatized that you don’t even know how not okay you are. You’ve never been this not okay before. You have been knocked so far into another reality that you don’t remember what okay is. Joy, peace, hope are all words you stare at but can no longer remember the meaning of, like when someone says “fork” over and over again.

I still went to work.

If I could have changed anything, I would have taken some time off work. My work, had they known what had happened, would have told me to not work.

But I didn’t tell them what happened, not really. I just kept working because I didn’t know what else to do.

I went to a work retreat in Oceanside, CA just a month after the bad thing happened, days after another fresh trauma.

At the retreat there was one day where we got to choose a fun activity.

Surfing was an option, but every time I’d tried surfing I’d been hit in the head with the surfboard and decided it was not fun.

Whale watching was an option, but I get seasick on small boats.

So I chose the Safari Park in Escondido.

We got a special tour and saw elephants and giraffes and zebras and cheetahs from far away. Then we went to a little sitting area in a small tent in the back where a zoo keeper brought out a few animals for us to get closer to. She brought out one white bird that perched on her forearm. She spoke to the bird as if to a friend, and the bird responded by swinging backwards in a kind of aerial silk routine, its claws clinging to her arm but it’s feathers upside down, swinging happily back and forth.

My eyes welled the second the bird flung itself backwards.

Later I would realize I cried because it was the first moment I remembered what joy was, remembered that just because I couldn’t feel it for a while didn’t it mean it wasn’t still here, in the feathers.

*

Even though you never play as Tess, Joel’s partner in the early part of the game, she was the one I dressed up as when I went to the Halloween Horror Nights behind the scenes tour so I could see The Last of Us house.

It wasn’t because I wanted to dress up like her to look cute (I don’t look good with my hair up the way she does). Just like I needed to play the game to get closer to the story, I needed to wear the clothes to get closer to that kind of hope, the kind you can pass on, even after you’re murdered by clickers, those once-human-now-bulbous-monsters that screeched and creeped their way towards me as I walked through the dark haunted house days later when I decided to actually go to the real thing and not just the lights-on tour.

I’d never been to a haunted house before and thought I never would. I blame you a little bit. I had to get closer to your story. When the tour guide said Ellie would stand above us and speak to us, that’s when I knew I had to go through the house when it was in its full scare glory.

I asked for a lot of advice. The advice I used the most was to smile at the monsters and say hello, because otherwise, people said, if they sensed your fear, they would come at you harder. If the monster in the next room heard you scream, they would be ready.

So the first time I saw a clicker, I smiled and said hello. I deeply hoped the actors didn’t think I was mocking them, that I didn’t appreciate the art of what this was. It certainly wasn’t me trying to be too cool for clicker school. In reality, the smiling was the only thing keeping me from falling apart.

I kept walking and smiling, trying to hold back a fear rising higher as each room narrowed.

About halfway through the house, just past a dark bathroom with pretty spores floating everywhere, into a hallway that felt like being inside of a bloater (i.e. clickers on steroids), something inside me broke. I became pure panic, felt fear as if it replaced my blood, as if I was really about to die for good. My brain could not reach my body fast enough.

I kept walking, knowing forward was my only real escape. I kept looking at every clicker. I can’t remember if I still smiled or not. But I never screamed.

I did have enough wits about me to look up and see Ellie, to hear her (and Ashley Johnson) say, “keep going.”

*

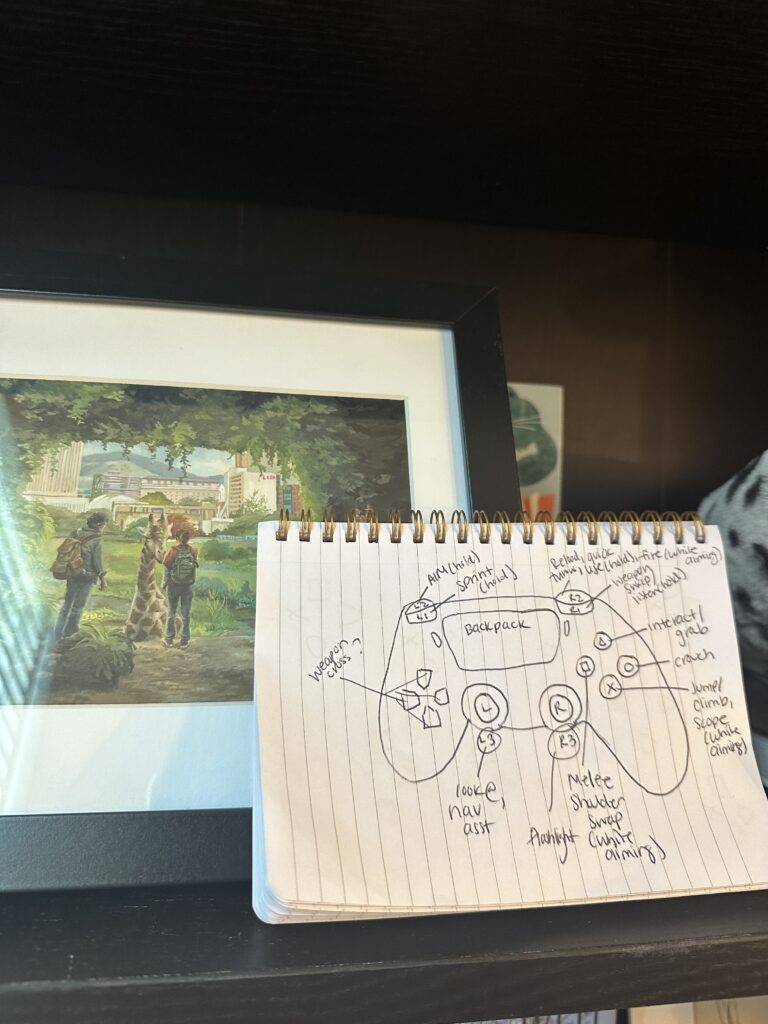

After my daughter dies and decades pass, me and Tess go on some mission before we meet Ellie. Before that first mission really even begins, I need to find a ladder so I can get into an abandoned building. I walked all over the lush grounds and could not find a ladder. I looked everywhere. I walked in circles, circles.

I was stuck. The game on easy mode and everything (thank you for easy mode, by the way, thank you thank you thank you. I would never have gotten to experience this without it).

Yet I still couldn’t find the ladder.

This was supposed to be fun. I was not having fun, again. I was stuck, again.

When is stuck fun and when is it not?

When is stuck worth sticking out and when is it a sign to move on?

Maybe I was not good at gaming. Maybe it would never be fun. The game has barely begun and I can’t even find a ladder.

I get mad, mostly at myself. Why am I so bad at this? Why am I so impatient? Why do I hate this part so much, this discomfort, this feeling lost, this not knowing, this being bad at something?

I keep spinning.

I remember the giraffes.

I first saw them in the TV show. I need to experience them for myself in the game.

I keep looking. I keep walking.

Eventually I find the ladder. It had been practically right in front of me the whole time; I just hadn’t been looking low enough to the ground.

*

When it was announced that The Last of Us was going to be a TV show I was thrilled. I’d watched the opening scene of the game once, at the recommendation of my brother. He said it was such a good story, and the word “story” got my attention.

I watched the first 30 minutes of the game, entranced. Yet, back then it didn’t even occur to me that I should play the game. I was decades-far outside of that world. I was just an observer, just here to see a story. It wasn’t even a question, a back and forth. It didn’t even occur to me that I could play it.

So instead, the first time I saw the opening, the first time I see Joel’s daughter die, I google “who made The Last of Us” and I learn the name “Neil Druckmann” and then I google that and then I read about you.

Of course it takes so many talented people to make a game (I watched the credits, and the documentary). (I’ve also been on a year-long hunt to try to find the person who made the towels in the opening scene in the PS5 remastered version, but no luck so far.)

There is no one person who can make a game like this one. But I do think one person can start something that attracts other talented people who can feel that vision and bring it to life.

Kind of like what it takes to make a TV show. Before I played the game, I watched the show. The show! I was so excited to have access to this story. I was not a gamer, but I was a TV-show-lover.

The show turned me inside out, as if I was a clicker, hungry for more information about the story and the storytellers.

Especially when the giraffes showed up.

*

Before the giraffes show up in the game, I am Ellie. I’m in the snow. I feel helpless. I’m no longer a man with all my tools and weapons. I’m a girl with almost nothing. It feels too familiar, and inexplicably sad. I think about how it felt to be Joel in comparison, less afraid to walk alone.

But I am walking alone, in the snow.

I run into a man. Two of them, actually.

What follows are horrors. Traumas. Ellie is changed. (I know you know this because you made this but I want you to know I know, you know?)

She reunites with Joel after the trauma. After being caged, chased, metaphorically skinned.

She’s not the same and Joel notices. She doesn’t smile. She doesn’t laugh. She doesn’t joke. Until now, she was the light and he the dark. Now her light is gone and he’s trying to find it and he can’t.

They keep walking, because they have somewhere they need to get to.

Am I Joel or Ellie here? I can no longer remember. All I remember is she was unhappy in a way I recognized.

And then—

They come upon a free roaming giraffe, poking its head through the broken building they’re in.

Ellie places her hand on the side of its cheek. She pauses for a moment, and then turns and runs up the stairs. Joel chases after her, asking her to slow down.

She just wanted to see the view. At a higher elevation, they can see many giraffes roaming in the clearing of what has been abandoned. “This everything you were hoping for?” Joel asks Ellie, referring to how little of the world she’d seen while being raised in a kind of confinement. “It’s got its ups and downs,” she replies.

*

After I finished playing The Last of Us Part I, I missed it immediately and bought things to fill the void. Like a replica of the backpack Ellie wears.

I carry it around for the first time at my final MFA residency, just before I graduate with an MFA in creative nonfiction. I was wearing it when the snow fell, when I walked a mile in it, when I crouched down to make my first snowman.

There was so much snow in The Last Of Us Part II. How do you feel about the snow? You spent a lot of growing up years in Florida, like me. But you also lived in New York some, like my dad. What did you think of the city, the snow, the heat?

Did you ever have a snowball fight?

The one that happens early on in Part II is the only one I’ve ever been a part of, and I loved it. The laughing while falling.

It was good to laugh in the beginning of Part II. What came next, as you know, was sorrow, horror, horror, sorrow, a kind of rhythm, with some longing thrown in. Oh and some guitar playing. The guitar!

Music helps, even when it hurts.

*

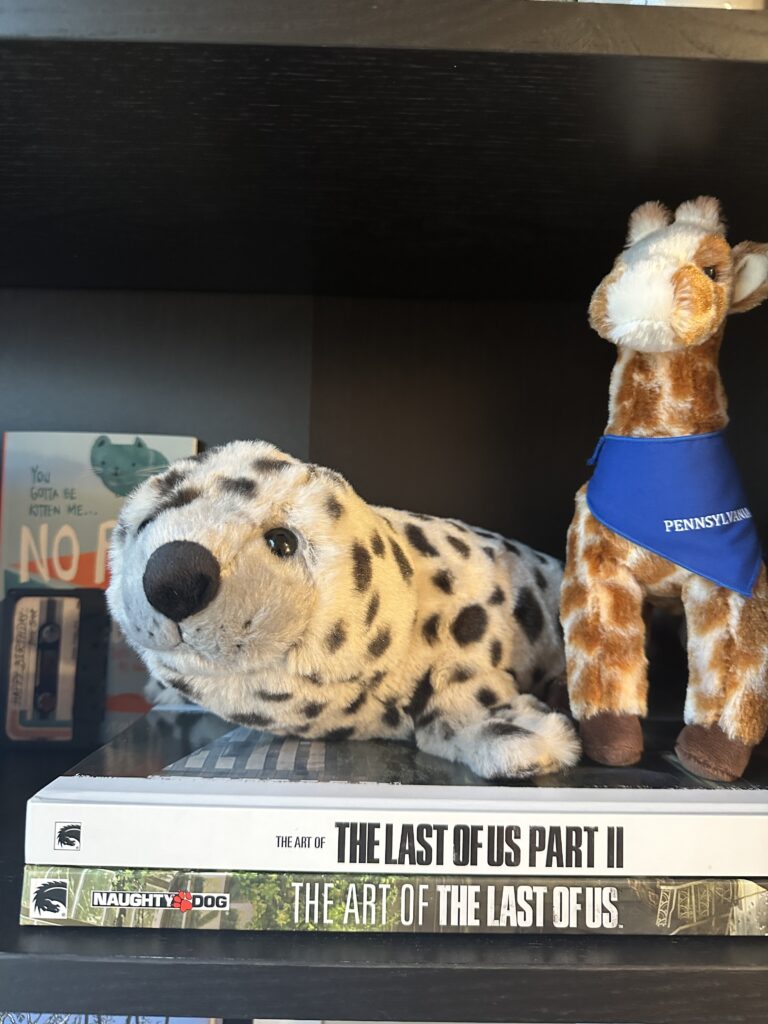

By the end of playing The Last of Us Part II I bought a stuffed spotted seal. I also have a giraffe tattoo on my right bicep.

I still think about the towels all the time, about how we affect everything we touch, everything we leave, everything we tend to, and don’t tend to.

I also can’t stop thinking about how halfway through Part II they start saying the names of people as they fall, as they die. I can’t stop thinking about the way that made me feel…kind of like the way I felt when, as Joel, I killed the nurses at the end of Part I; it happened so fast, the way I had been in a rhythm of shoot and run, survive, survive, survive, so caught in that trap that I didn’t stop to realize I had another choice.

*

A few weeks ago in an airport, after a delay, I pulled out my Nintendo Switch and played Donkey Kong. I kept dying, as always, but I kept going too. I beat a level I’d been stuck on for 20 years.

Thank you,

Isa

The Little Book of Big Dreams is filled with true stories of dreamers who decided to try for their biggest dreams and kept going when things got hard (which they almost always do).

The dreamers in this book include Oscar winner Kristen Anderson-Lopez, Disney producer Don Hahn, Pensole Lewis College founder D’Wayne Edwards, Hamilton cast member Seth Stewart, Black Girls Code founder Kimberly Bryant, and more.

But the most important story in this book is yours.

The Little Book of Big Dreams: True Stories about People Who Followed a Spark

order The Little Book Of Big Dreams

spark your next dream

© Chronicle | Legal | Site Credit |